Covid-19: why the lab leak theory must be formally investigatedVirginie Courtier, Université de Paris and Etienne Decroly, Aix-Marseille Université (AMU)A year and a half into the pandemic, we still do not know exactly where the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes Covid-19, came from. The prevailing view so far has been that the virus “spilled over” from bats into humans. But there are increasing calls to investigate the possibility that it emerged from a lab in Wuhan, China, where Covid first appeared at the end of 2019. So what do we know for sure, and what do we need still to find out? We know the sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is close to that of bat coronaviruses. Several decades ago its “ancestor” was circulating in bat populations in southern Asia. But there are still many unanswered questions: we don’t know how the virus arrived in Wuhan, how its sequence evolved to allow human infection, and under what conditions it infected the first people who crossed its path. And for each of these stages, we don’t know whether there was a human contribution (direct or indirect). Lire cet article en français: “Origine de la Covid-19 : l’hypothèse de l’accident de laboratoire doit-elle être étudiée d’un point de vue scientifique ?” Zoonotic transmission pathways, in other words the passage of viruses from animals to humans, are now widely documented around the world. Scientists even consider that this is a principal mechanism for the spreading of new viruses. But the fact that the pandemic began in the vicinity of a main virus research centre that specialises in the study of coronaviruses with epidemic potential in humans – the Wuhan Institute of Virology – has given rise to another hypothesis, the lab leak theory. Lab accidents have already led to human infections, including the H1N1 flu pandemic of 1977, which killed more than 700,000 people. Which theory is correct? In the absence of definitive proof, and without promoting conspiracy theories, there needs to be a serious international conversation about the origin of SARS-CoV-2. The zoonosis theoryIn the scientific community, the debate on the origin of SARS-CoV-2 started with the publication of two articles at the very beginning of the outbreak. The first, dated February 19, 2020, was published in the medical science journal The Lancet. This article, signed by 27 scientists, highlighted the efforts of Chinese experts to identify the source of the pandemic and share the results. The authors deplored “rumours and misinformation” about the origins of the virus, and stated that they “strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that Covid-19 does not have a natural origin”. The authors based their opinion on the first published sequence data, but did not detail the scientific arguments supporting a natural origin. In March 2020, another article published in Nature Medicine provided a series of scientific arguments in favour of a natural origin. The authors argued:

This last argument can be questioned, as methods do exist which allow scientists to modify viral sequences without leaving a trace. These include cutting the genome into fragments that can later be joined together or, more recently, using the ISA protocol, whereby overlapping fragments naturally come together in cells through homologous recombination: a phenomenon in which two DNA molecules exchange fragments. Besides, genetic manipulation is not the only scenario compatible with a laboratory accident or leak. Meanwhile, intense research that has been carried out for more than a year to try to prove the zoonotic scenario has not been successful so far: all 80,000 animal samples, from some 30 species, have tested negative. The samples came from farm animals and wild animals from different provinces in China. But it is important to note that this large number of negative samples does not refute the zoonotic scenario. The lab theoryThe first articles arguing for the laboratory accident theory received little attention, perhaps because they came from groups like the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which tends to be critical of technology, or outsiders such as the DRASTIC team (an acronym for “decentralized radical autonomous search team investigating Covid-19”). Composed of 24 self-styled “Twitter detectives” who are mostly anonymous with the exception of a few scientists participating under their real names, the DRASTIC group formed on Twitter in 2020 and has set itself the mission of exploring the origins of SARS-CoV-2. Information and arguments from the group have been examined in their own right, taken up and developed by some virologists, microbiologists and science communicators. In July 2020, one of the authors of this article, Etienne Decroly, co-wrote a scientific paper discussing the possibility of a laboratory accident. The lab leak theory gained wider traction after a May 13 article in the journal Science, signed by 18 scientists, called again for the origins of SARS-CoV-2 to be examined.

So is it possible? Several elements regarding the emergence of the virus do raise questions. In particular, it has been established that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was handling viruses close to SARS-CoV-2 collected in southern China. In addition to direct genetic manipulation, a laboratory accident could also have occurred as a result of infection during collection in the wild or during an experiment with a virus that evolved in cells or mice in the laboratory, without necessarily directly manipulating its genome. How can we find out for sure?In an investigation at the start of this year, a joint commission between China and the World Health Organization (WHO) failed to identify the cause of the pandemic, concluding that a zoonotic origin is most likely and the hypothesis of a laboratory accident is very unlikely. But the director-general of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, announced there were still questions that “will need to be addressed by further studies”. Determining whether SARS-CoV-2 has escaped from a laboratory will require a more thorough investigation in which investigators have access to sequence databases as well as to the various resources used by Chinese researchers, including laboratory notebooks, submitted projects, scientific manuscripts, viral sequences, order lists and biological analyses. Unfortunately, sequence databases for SARS-CoV-2 have been inaccessible to scientists since September 2019. In the absence of direct evidence, alternative approaches may provide additional information. By analysing the available sequences of SARS-CoV-2-like coronaviruses in detail, it is possible that the scientific community will reach a consensus based on strong clues, as they did for other outbreaks, including the 1977 H1N1 virus. Biological black boxesWhether the origin is zoonotic or not, it is necessary to question the consequences of our interactions with ecosystems, the industrialisation of intensive breeding, safety protocols on collecting and experimenting on potentially pandemic viruses, and the proliferation of high-security laboratories, particularly those near megacities. We need to equip facilities that study viruses with safety systems as demanding as those used for studying nuclear energy. This could include the introduction of “biological black boxes”, similar to flight recorders which allow investigators to recreate the final moments of a plane accident. Access to certain high-risk labs could be made dependent on detailed digital descriptions of experiments; sequencing data could be systematically archived; laboratory air filters could be collected, and if there is a suspicion of pathogen dissemination, the genetic material on their surface could be sequenced. Such new safety measures should be put in place internationally to limit the risk of future pandemics. As for SARS-CoV-2, it is important to trace its exact origins in order to understand precisely what flaws may have led to its spread. Virginie Courtier, Directrice de recherche CNRS, génétique et évolution, Université de Paris and Etienne Decroly, Directeur de recherche en virologie, Aix-Marseille Université (AMU) This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Additional Source:

I posted the Guardian article on Facebook:

ALSO VERY INTERESTING: In 1965, researchers discovered a vexing respiratory infection called 229E. Today, we know it as the common cold.

Russel Brand explores:

Science writer Nicholas Wade has written an article in which he concludes that evidence around the origins of COVID-19 is “fairly firmly in favour” of the virus coming from the lab at Wuhan. With other scientists contesting his reasoning, what does this scientific debate signify?

A series of protests against unreasonable Corona restrictions - Flashmobs in various places:

Paris

Liberté ! "DANSER ENCORE" - Flashmob - Le Sénat - 1 Mai 2021

Flashmob organisé le 1er Mai 2021 à Paris, dans les Jardins du Sénat.

One of the comments under this video:

More Videos from around Europe:

The official Version started in December 2020

One comment:

It's the New World anthem! That of fraternity, of conscience, of the joy of dancing life together! Will the end of the COVID-19 pandemic usher in a second Roaring ’20s?

While some places remain mired in the third wave of the pandemic, others are taking their first tentative steps towards normality. Since April 21, Denmark has allowed indoor service at restaurants and cafes, and football fans are returning to the stands. In countries that have forged ahead with the rollout of vaccines, there is a palpable sense of optimism. And yet, with all this looking forward, there is plenty of uncertainty over what the future holds. Articles on what the world will look like post-pandemic have proliferated and nations worldwide are considering how to recover financially from this year-long economic disaster. Almost exactly a hundred years ago, similar conversations and preparations were taking place. In 1918, an influenza pandemic swept the globe. It infected an estimated 500 million people — around a third of the world’s population at the time — in four successive waves. While the end of that pandemic was protracted and uneven, it was eventually followed by a period of dramatic social and economic change. The Roaring ‘20s — or “années folles” (“crazy years”) in France — was a period of economic prosperity, cultural flourishing and social change in North America and Europe. The decade witnessed a rapid acceleration in the development and use of cars, planes, telephones and films. In many democratic nations, some women won the right to vote and their ability to participate in the public sphere and labour market expanded. Parallels and differencesAs a historian of health care, I see some striking similarities between then and now, and as we enter our very own '20s it is tempting to use this history as a way of predicting the future. Vaccine rollouts have raised hope for an end to the COVID-19 pandemic. But they’ve also raised questions about how the world might bounce back, and whether this tragic period could be the start of something new and exciting. Much like in the 1920s, this disease could prompt us to reconsider how we work, run governments and have fun. However, there are some crucial differences between the two pandemics that could alter the trajectory of the upcoming decade. For one, the age-profile of the victims of the influenza pandemic was unlike that of COVID-19.

The 1918 flu — also called the Spanish flu — predominantly affected the young, whereas COVID-19 has mostly killed older people. As a result, fear probably refracted through the two societies in different ways. Young people have certainly been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: the virus has posed a threat to those with underlying health conditions or disabilities of all ages, and some of the variants have been more likely to affect younger people. A year of lockdowns and shelter-in-place orders has had a damaging effect on mental and emotional health, and young people have experienced increased anxiety. Read more: COVID-19’s parallel pandemic: Why we need a mental health 'vaccine' However, the relief of surviving the COVID-19 pandemic might not feel quite the same as that experienced by those who made it through the 1918 influenza pandemic, which posed an immediate risk of death to those in their 20s and 30s. 1918 vs. 2020Crucially, the 1918 flu came immediately after the First World War, which produced its own radical reconstitution of the social order. Despite the drama and tragedy of 2020, the changes we are living through now might be insufficient to produce the kind of social transformation witnessed in the 1920s. One of the key features of the Roaring '20s was an upending of traditional values, a shift in gender dynamics and the flourishing of gay culture.

While the prospect of similar things happening in the 2020s might seem promising, the pandemic has reinforced, rather than challenged, traditional gender roles. There is evidence for this all over the world, but in the United States research suggests that the risk of mothers leaving the labour force to take up caring responsibilities at home amounts to around US$64.5 billion per year in lost wages and economic activity. When most people think of the Roaring '20s they probably call to mind images of nightclubs, jazz performers and flappers — people having fun. But fun costs money. No doubt, there will be plenty of celebration and relief when things return to a version of normality, but hedonism will probably be out of reach for most. Young people in particular have been hard hit by the financial pressures of COVID-19. Workers aged 16-24 face high unemployment and an uncertain future. While some have managed to weather the economic storm of this past year, the gap between rich and poor has widened. Inequality and isolationismOf course, the 1920s was not a period of unadulterated joy for everyone. Economic inequality was a problem then just as it is now. And while society became more liberal in some ways, governments also enacted harsher and more punitive policies, particularly when it came to immigration — specifically from Asian countries. The Immigration Act of 1924 limited immigration to the U.S. and targeted Asians. Australia and New Zealand also restricted or ended Asian immigration and in Canada, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 imposed similar limitations. There are troubling signs that this might be the main point of similarity between then and now. Anti-Asian sentiment has increased and many countries are using COVID-19 as a way of justifying harsh border restrictions and isolationist policies. In our optimism for the future, we must remain alert to all the different kinds of damage the pandemic could cause. Just as disease can be a mechanism for positive social change, it can also entrench inequalities and further divide nations and communities. Agnes Arnold-Forster, Researcher, History of Medicine and Healthcare, McGill University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Diesmal keine Übersetzung auf Englisch - das leitende Video ist ja auf Deutsch, also würde das im Zusammenhang mit meinem folgenden Text (sowie weiterem Video) wenig Sinn für meine Englisch sprechenden Freunde machen.

Dr. Wolfgang Wodarg - Wie kommt es zu Blutgerinnseln nach der Corona-Impfung?

Dr. Wolfgang Wodarg erklärt den Zusammenhang zwischen der Impfung und den Thrombosen, Schlaganfällen und Lungenembolien. +++Astrazeneca heißt jetzt auch Vaxzevria.+++ Note: the video originally embedded here disappeared also, here is the same one embedded from another source. Should this again malfunction, I have a copy of it saved as well.

Ich suchte solch Video um es als Kommentar zu einem Facebook Eintrag über den neuen Gesundheitsminister in Österreich, Dr. Wolfgang Mückstein einzustellen. Das Facebook Video ist eine Zusammenfassung einer Servus-TV Sendung vom März 2021:

Jetzt kann man sich vorstellen was auf uns zukommt. Wir werden uns in Zukunft noch wehmütig an den "Angstschober" erinnern. Also das hier wird der neue Impf- und Kerkermeister.

Recherchen über dieses Thema. Hier handelt es sich um Aspirieren von Impfungen

(Forum Deutsches Ärzteblatt): Verzicht auf Aspiration bei i.m. Injektion?

Um nochmal das Thema über Aspirieren aufzugreifen, ich zitiere:

Aspirieren, d. h. die Spritze in der Position halten und den Spritzenstempel leicht zurück ziehen, um einen Gefäßanstich auszuschließen. Kommt Blut, Injektion sofort stoppen, Kanüle entfernen, Einstichstelle abdrücken.

Ich muss aber zugeben dass ich kein begeisterter Freund der derzeitigen Bundesregierung bin. Es ist kein Geheimniss dass ich die "Maßnahmen" für überzogen halte und deshalb schon öfters ins rechte Verschwörungstheoretiker Eck gestellt wurde. Schon vor der Angelobung des neuen Gesundheitsministers habe ich kommentiert wir werden uns noch mit Sehnsucht an den "Angstschober" (Rudolf Anschober, zurückgetreten) erinnern, denn was auf uns jetzt zukommt ist "besorgnisserregend".

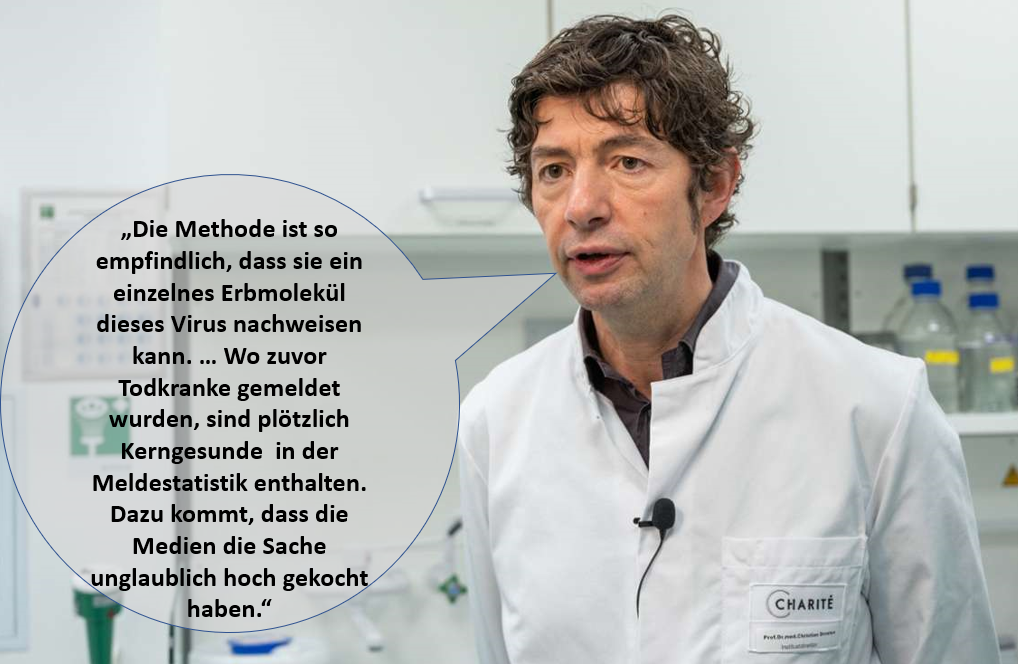

A debatable subject - to take a quote out of context:

"But your body also produces antibodies as a response to vaccination. That’s the way it can recognise SARS-CoV-2, the next time it meets it, to protect you from severe COVID. So as COVID vaccines are rolled out, and people develop a vaccine-induced antibody response, it may become difficult to differentiate between someone who has had COVID in the past and someone who was vaccinated a month ago." Will the COVID vaccine make me test positive for the coronavirus? 5 questions about vaccines and COVID testing answered

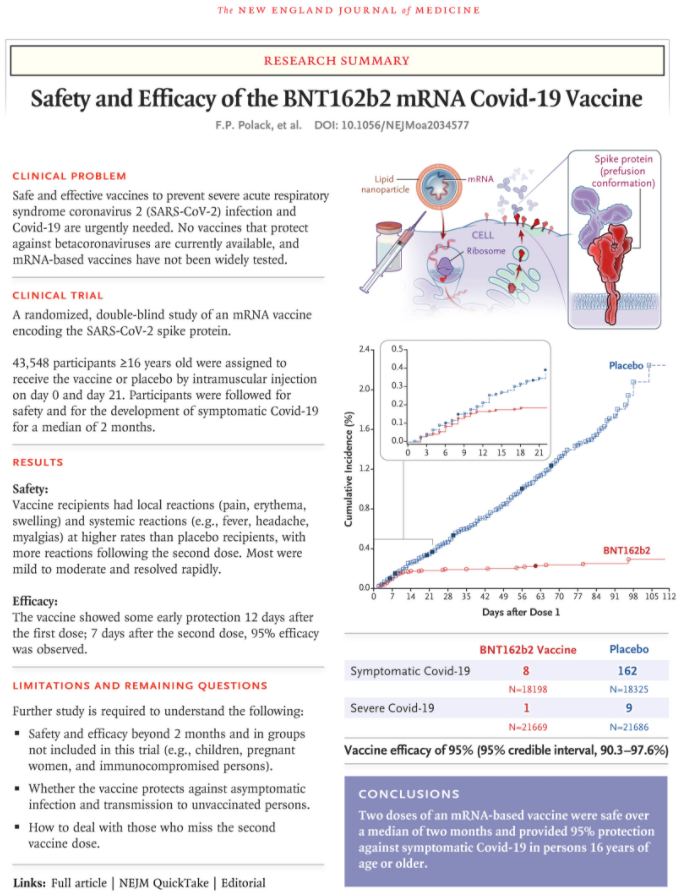

COVID-19 vaccination is rolling out across Australia. So health authorities are keen to dispel myths about the vaccines, including any impact on COVID testing. Do the vaccines give you COVID, or make you test positive for COVID? Does the vaccine affect other tests? Do we still need to get COVID tested if we have symptoms, even after getting the shot? And will we still need COVID testing once more of the population gets vaccinated? We look at the evidence to answer five common questions about the impact of COVID vaccines on testing. 1. Will the vaccine give me COVID?The short answer is “no”. That’s because the vaccines approved for use so far in Australia and elsewhere don’t contain live COVID virus. The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine contains an artificially generated portion of viral mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid). This carries the specific genetic instructions for your body to make the coronavirus’s “spike protein”, against which your body mounts a protective immune response. The AstraZeneca vaccine uses a different technology. It packages viral DNA into a viral vector “carrier” based on a chimpanzee adenovirus. When this is delivered into your arm, the DNA prompts your body to produce the spike protein, again stimulating an immune response. Any vaccine side-effects, such as fever or feeling fatigued, are usually mild and temporary. These are signs the vaccines are working to boost your immune system, rather than signs of COVID itself. These symptoms are also common after routine vaccines. 2. Will the COVID vaccine make me test positive?No, a COVID vaccine will not affect the results of a diagnostic COVID test. The current gold-standard diagnostic test is known as nucleic acid PCR testing. This looks for the mRNA (genetic material) of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. This is a marker of current infection. This is the test the vast majority of people have when they line up at a drive-through testing clinic, or attend a COVID clinic at their local hospital. Yes, the Pfizer vaccine contains mRNA. But the mRNA it uses is only a small part of the entire viral RNA. It also cannot make copies of itself, which would be needed for it to be in sufficient quantity to be detected. So it cannot be detected by a PCR test. The AstraZeneca vaccine also only contains part of the DNA but is inserted in an adenovirus carrier that cannot replicate so cannot give you infection or a positive PCR test. 3. How about antibody testing?While PCR testing is used to look for current infection, antibody testing — also known as serology testing — picks up past infections. Laboratories look to see if your immune system has raised antibodies against the coronavirus, a sign your body has been exposed to it. As it takes time for antibodies to develop, testing positive with an antibody test may indicate you were infected weeks or months ago. But your body also produces antibodies as a response to vaccination. That’s the way it can recognise SARS-CoV-2, the next time it meets it, to protect you from severe COVID. So as COVID vaccines are rolled out, and people develop a vaccine-induced antibody response, it may become difficult to differentiate between someone who has had COVID in the past and someone who was vaccinated a month ago. But this will depend on the serology test used. Read more: Antibody tests: to get a grip on coronavirus, we need to know who's already had it The good news is that antibody testing is not nearly as common as PCR testing. And it’s only ordered under limited and rare circumstances. For instance, when someone tests positive with PCR, but they are a false positive due to the characteristics of the test, or have fragments of virus lingering in the respiratory tract from an old infection, public health experts might request an antibody test to see whether that person was infected in the past. They might also order an antibody test during contact tracing of cases with an unknown source of infection. Read more: Why can't we use antibody tests for diagnosing COVID-19 yet? 4. If I get vaccinated, do I still need a COVID test if I have symptoms?Yes, we will continue to test for COVID as long as the virus is circulating anywhere in the world. Even though the COVID vaccines are looking promising in preventing people from getting seriously sick or dying, they won’t provide 100% protection. Real-world data suggests some vaccinated people can still catch the virus, but they usually only get mild disease. We are unsure whether vaccinated people will be able to potentially pass it to others, even if they don’t have any symptoms. So it’s important people continue to get tested.

Furthermore, not everyone will be eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. For instance, in Australia, current guidelines exclude people under 16 years of age, and those who are allergic to ingredients in the vaccine. And although pregnant women are not ruled out from receiving the vaccine, it is not routinely recommended. This means a proportion of the population will remain susceptible to catching the virus. We also are unsure about how effective vaccines will be against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. So we will continue to test to ensure people are not infected with these strains. We know testing, detecting new cases early and contact tracing are the core components of the public health response to COVID, and will continue to be a priority from a public health perspective. Minimum numbers of daily COVID tests are also needed so we can be confident the virus is not circulating in the community. As an example, New South Wales aims for 8,000 or more tests a day to maintain this peace of mind. Continued vigilance and high rates of testing for COVID will also be important as we enter the flu season. That’s because the only way to differentiate between COVID and influenza (or any other respiratory infection) is via testing. 5. Will testing for COVID stop as time goes on?It is unlikely our approach to COVID testing will change in the immediate future. However, as COVID vaccines are rolled out and since COVID is likely to become endemic and stay with us for a long time, the acute response phase to the pandemic will end. So COVID testing may become part of managing other infectious diseases and part of how we respond to other ongoing health priorities. Read more: Coronavirus might become endemic – here's how Meru Sheel, Epidemiologist | Senior Research Fellow, Australian National University; Charlee J Law, Epidemiologist | Research Associate, Australian National University, and Cyra Patel, PhD candidate, Australian National University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image by Ria Sopala from Pixabay

To keep our immune system in top condition it is important that we pay particular attention to the problem of fine particle pollution. There isn't a vaccine that can do this for us: we have to drastically change our lifestyles. In fact, pollution can, as the video below explains, turn our immune system against us and cause reactions that are responsible for many major illnesses, including cancer. This is explained in the video below:

What impact does the inhalation of fine particles have on our Immune system

Here is a article from THE CONVERSATION that dates back to November 15th 2018 that deals extensively with this problem, and I reprint it here in its entirety:

Fine particle air pollution is a public health emergency hiding in plain sight

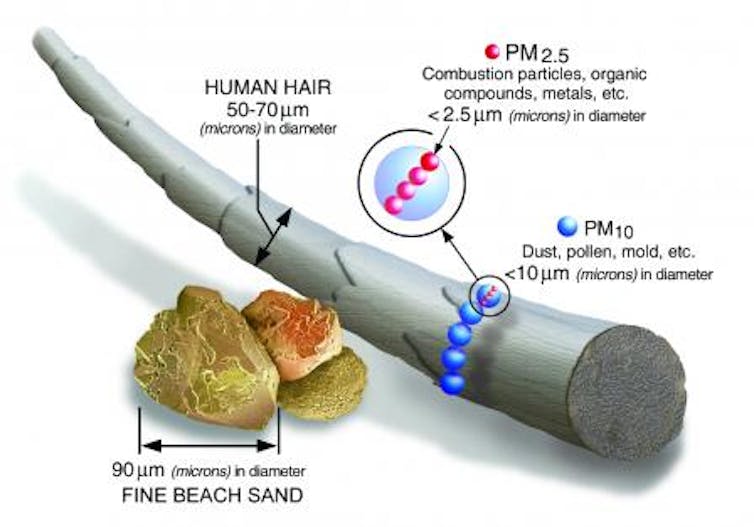

Ambient air pollution is the largest environmental health problem in the United States and in the world more generally. Fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 millionths of a meter, known as PM2.5, was the fifth-leading cause of death in the world in 2015, factoring in approximately 4.1 million global deaths annually. In the United States, PM2.5 contributed to about 88,000 deaths in 2015 – more than diabetes, influenza, kidney disease or suicide. Current evidence suggests that PM2.5 alone causes more deaths and illnesses than all other environmental exposures combined. For that reason, one of us (Douglas Brugge) recently wrote a book to try to spread the word to the broader public. Developed countries have made progress in reducing particulate air pollution in recent decades, but much remains to be done to further reduce this hazard. And the situation has gotten dramatically worse in many developing countries – most notably, China and India, which have industrialized faster and on vaster scales than ever seen before. According to the World Health Organization, more than 90 percent of the world’s children breathe air so polluted it threatens their health and development. As environmental health specialists, we believe the problem of fine particulate air pollution deserves much more attention, including in the United States. New research is connecting PM2.5 exposure to an alarming array of health effects. At the same time, the Trump administration’s efforts to support the fossil fuel industry could increase these emissions when the goal should be further reducing them.

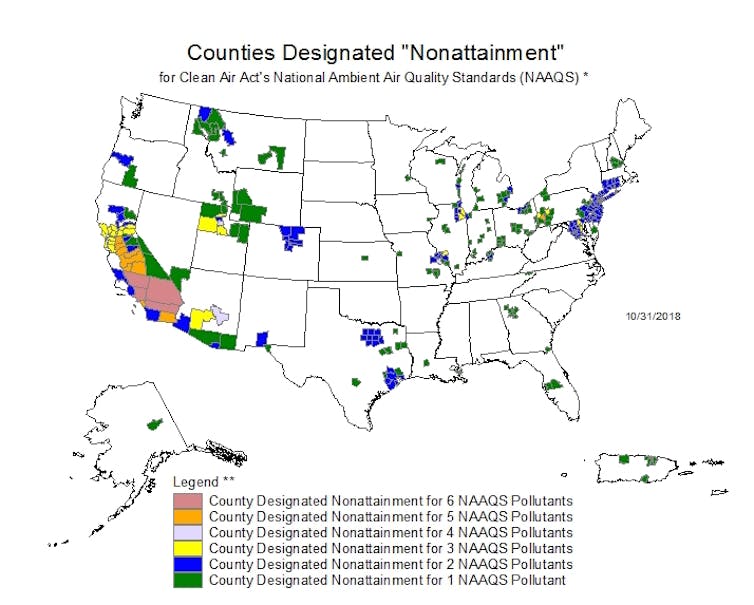

Where there’s smoke …Particulate matter is produced mainly by burning things. In the United States, the majority of PM2.5 emissions come from industrial activities, motor vehicles, cooking and fuel combustion, often including wood. There is a similar suite of sources in developing countries, but often with more industrial production and more burning of solid fuels in homes. Wildfires are also an important and growing source, and winds can transport wildfire emissions hundreds of miles from fire regions. In August 2018, environmental regulators in Michigan reported that fine particles from wildfires burning in California were impacting their state’s air quality. Most deaths and many illnesses caused by particulate air pollution are cardiovascular – mainly heart attacks and strokes. Obviously, air pollution affects the lungs because it enters them as we breathe. But once PM enters the lungs, it causes an inflammatory response that sends signals throughout the body, much as a bacterial infection would. Additionally, the smallest particles and fragments of larger particles can leave the lungs and travel through the blood. Emerging research continues to expand the boundaries of health impacts from PM2.5 exposure. To us, the most notable new concern is that it appears to affect brain development and has adverse cognitive impacts. The smallest particles can even travel directly from the nose into the brain via the olfactory nerve. There is growing evidence that PM2.5, as well as even smaller particles called ultrafine particles, affect children’s central nervous systems. They also can accelerate the pace of cognitive decline in adults and increase the risk in susceptible adults of developing Alzheimer’s disease. PM2.5 has received much of the research and policy attention in recent years, but other types of particles also raise concerns. Ultrafines are less studied than PM2.5 and are not yet considered in risk estimates or air pollution regulations. Coarse PM, which is larger and typically comes from physical processes like tire and brake wear, may also pose health risks. Regulatory push and pullThe progress that developed countries have made in addressing air pollution, especially PM, demonstrates that regulation works. Before the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970, air quality in Los Angeles, New York and other major U.S. cities bore a striking resemblance to Beijing and Delhi today. Increasingly stringent air pollution regulations enacted since then have protected public health and undoubtedly saved millions of lives. But it wasn’t easy. The first regulatory limits on PM2.5 were proposed in the 1990s, after two important studies showed that it had major health impacts. But industry pushback was fierce, and included accusations that the science behind the studies was flawed or even fraudulent. Ultimately federal regulations were enacted, and follow-up studies and reanalysis confirmed the original findings. Now the Trump administration is working to reduce the role of science in shaping air pollution policy and reverse regulatory decisions by the Obama administration. One new appointee to the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, Robert Phalen, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine, is known for asserting that modern air is actually too clean for optimal health, even though the empirical evidence does not support this argument.

On Oct. 11, 2018, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler disbanded a critical air pollution science advisory group that dealt specifically with PM regulation. Critics called this an effort to limit the role that current scientific evidence plays in establishing national air quality standards that will protect public health with an adequate margin of safety, as required under the Clean Air Act. Opponents of regulating PM2.5 in the 1990s at least acknowledged that science had a role to play, although they tried to discredit studies that supported the case for regulation. The new approach seems to be to try to cut scientific evidence out of the process entirely. No time for complacencyIn late October 2018, the World Health Organization convened a special conference on global air pollution and health. The agency’s heightened interest appears to be motivated by risk estimates that show air pollution to be a concern of similar magnitude to more traditional public health targets, such as diet and physical activity. Conferees endorsed a goal of reducing global deaths from air pollution by two-thirds by 2030. This is a highly aspirational target, but it may focus renewed attention on strategies such as reducing economic barriers that make it hard to deploy pollution control technologies in developing countries. In any case, past and current research clearly show that now is not the time to move away from regulating air pollution that arises largely from burning fossil fuels, in the United States or abroad. Doug Brugge, Professor of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University and Kevin James Lane, Assistant Professor of Environmental Health, Boston University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image by ❤️ Remains Healthy ❤️ from Pixabay

Yes - proof positive FACEBOOK IS BEING STUPID!

This is from the USA Conversation, and I am posting from Austria!!!!! There are no Kangaroos in Austria, you Zuckerberg Morons! Quote: In response to Australian government legislation, Facebook restricts the posting of news links and all posts from news Pages in Australia. Globally, the posting and sharing of news links from Australian publications is restricted. Subsequently, I shared this on Facebook from my Twitter Feed: How the media may be making the COVID-19 mental health epidemic worse This happened to me yesterday already when I tried to share a UK Conversation Article, but yesterday there was no warning, just a error message, and subsequently I posted a question on Facebook which caused a lot of head scratching, until he mystery got solved today. Eventually, I resorted to the same "trick" of posting my Twitter feed. From trippy drugs to therapeutic aids – how psychedelics got their groove back Both of these articles are highly recommended to read, they deal directly, and the second one indirectly, with Corona Virus issues, so please follow the links. corona updats from my blockchain account on peakdI realized that I have not updated this blog since end of November - but I did post since then on my Blockchain account about the subject, as well as reposted relevant information from others. Here is a selection of topics in descending order. The images link to the respective articles and open in a separate window. NOTE: some blogs are in German and some in English only. A few may be at least partially bilingual. When necessary, use Google Website Translate. Lockdown in Wien als Horror-Survival-Game a free game about the lockdown - collect toilet paper to survive I think I got most of the blogs on my PeakD site for these past few months that I think are good reads and contain important information. Stay tuned for another summary soon - I had compiled a lot of information that is very relevant to our current situation, about the WHO Definition of Herd Immunity and related subject matter.

I wear a mask because it is mandated (in this case in public transport), but not because I am convinced it is necessary. I wear it because I don't feel like arguing with law enforcement or self-appointed blockwarts about it. Why do I think it is not necessary? Lets see: this mask does not protect me from infection, and I hope everyone knows this. It is supposed to protect others from catching the virus from me. In my case, illogical: I am by age and precondition in the high risk group. Should I be infected (i.e. contagious to others) I would not be here, sitting in the S-Bahn, apparently healthy, but I would most likely be lying in a hospital bed or maybe even in the ICU.

Now the Austrian Government and their esteemed scientific advisers in their deep and unassailable wisdom had declared that face shields do not qualify as MNS (mouth-nose protection) because there are gaps, and that said MNS have to be reasonably tight fitting. But as I said above, they do nothing to protect me. What would protect me would be the equivalent of a N95 mask (or better, see link below), and because of my breathing problems due to my precondition, I need one with an exhale valve. I am thinking of getting one. The "regulations" did not even mention those, just face shields. And I see more of them now also on public transport, supermarkets and wherever masks are legally required. Now understand this - the regulations talk about masks, but there is a difference between a mask and a respirator. Perhaps the Government, and its Experts (using the term rather loosely), would need a refresher course. Furthermore, most workplace health and safety regulations require that masks should not be worn for more than 2 hours straight. A free breathing pause should be made for ideally half hour. So what about a train ride from Vienna to Bregenz, for example, that takes 9 hours, or a flight between Vienna and Calgary that takes 12 hours? You must wear a mask for the entire time! Before anyone interjects with "what about operating room personnel that operate for hours on end" there is an answer also: they wear surgical masks that are not tight fitting, and the operating room has enhanced air circulation with oxygen enrichment. But let us assume you are symptomatic: The normal way of getting rid of intruders from your airways is through sneezing and coughing. In this case, a virus load. You also expel viruses by simply breathing out (hence the mask requirement). But instead of getting rid of them, they hang in the mask and you then breathe them back in. So you are sort of re-infecting yourself, increasing your virus load more. This could be a problem for people who are already infected, making the infection worse. Now think about old people in nursing homes who are made to wear mask. I used to teach respirator protocol and safety - this here is a good guide:

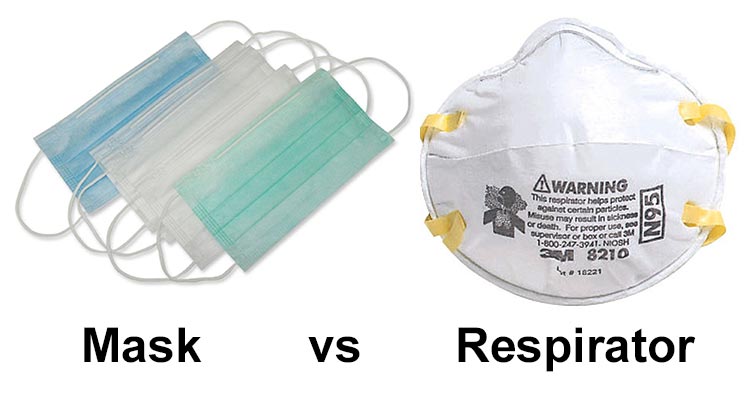

Masks vs Respirators

Before we go any further, let’s just clarify on a technical difference between a “mask” and a “respirator”. In day to day language we often say mask, when referring to what are technically called respirators.

In my estimation, the best resource about the subject, there is a lot of very good information and relevant links on that site, so click here or else the image above to read more.

Image by Avi Chomotovski from Pixabay

Domestic abuse and mental ill-health: twin shadow pandemics stalk the second wave

The coronavirus crisis has been stalked by two shadow pandemics – one of domestic abuse and one of mental health. Since the first outbreak of the virus, numerous reports have highlighted a marked increase in forms of domestic violence and abuse, especially intimate partner violence and domestic homicide. The pandemic has also been linked to rising rates of mental health issues around the world. These two phenomena are intrinsically linked: research shows there is a strong association between mental ill-health and domestic abuse. This raises significant concerns as a second wave of the pandemic crashes upon us. Cities, regions and whole countries are going back into lockdown – a measure that has previously been reported to have increased rates of both domestic violence and mental health problems. This time around, we need to be better prepared to support victims and survivors. Lockdowns exacerbate domestic abuseUN Secretary General Antonio Guterres has described the rise in domestic violence in 2020 as a “horrifying global surge”. Evidence compiled by UN Women from the UK, the United States, France, Australia, Cyprus, Singapore, Argentina, Canada, Germany, and Spain shows a rise in demand for access to women’s refuges and other support services this year. The UK charity Refuge reported a 700% increase in calls during a single day in April and by June calls had risen by 800% compared with pre-lockdown figures. The charity also reported a 300% increase in visits to its National Domestic Abuse Helpline website and a 950% rise in visits to their website. Read more: Domestic violence shadow pandemic has not gone away after lockdown It is likely that these statistics reflect a glimpse of the overall picture given the known difficulties of reporting abuse, which are now intensified for households where the perpetrator is more frequently or consistently at home due to COVID-19 measures. The incidence and prevalence of domestic violence does tend to increase during any stressful event or emergency, whether it is a natural disaster, or whether it is man-made. The surge in domestic violence has not just been associated with instructions to stay home, but also linked to the economic and social stresses on households that have resulted from this pandemic. These include the growth in unemployment, uncertainty around furloughing and job security and the effects of social isolation. The toll on mental healthThe results of COVID-19 measures on mental ill-health have been widely covered with concerns that further mental health devastation is imminent as we face a second wave. Infection control measures such as social distancing and shielding lead to a higher risk of mental health problems such as anxiety, fear and sleep disturbances for general populations and can aggravate symptoms for people living with existing mental health conditions. Research shows women who experience abuse from their partner are three times more likely to suffer depression, anxiety or severe conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Whether these are new or pre-existing problems, this impact is likely to be severe and long-lasting, resulting in more demands placed on already overburdened mental health systems. The conditions associated with the pandemic have presented heightened risks and barriers to those who want to seek help. People’s means and opportunity to contact services may be restricted and access to support networks might be limited or wholly unreachable. Those with existing mental health conditions might have limited access or difficulty accessing medication or therapy which, in turn, exacerbates mental ill-health. This can trigger self-harm, substance use or suicidal ideation. Every day in the UK, almost 30 women attempt suicide and every week three women take their own lives to escape domestic abuse. Taking on two problems at onceAs we are now at the onset of a second wave of the pandemic, it is likely we’ll see another surge in domestic abuse and its associated negative impacts on mental health. Obstacles to accessing support will continue and perhaps multiply during further lockdowns and services will remain frustrated by persistent underfunding and deficient resources in the face of greater demands. Two already overburdened systems risk becoming even more frayed at the edges in the months to come. To respond to the severe, long-lasting impacts of domestic abuse and mental ill-health following COVID-19, governments should invest in evidence-based research and mainstream interventions that target the connections between the two phenomena. This includes screening for both domestic abuse and mental health problems by practitioners across both sectors, providing online interventions and safety planning. Governments should also encourage different services to work together, through more substantial funding and a policy response which recognises and responds to these overlapping issues. COVID-19 will not be the last emergency we face with the potential to increase rates of domestic abuse and mental ill-health. We should use the lessons we have learned from this pandemic to prepare ourselves to better respond to other crises in future. These lessons can also help us understand the impact of emergencies on those experiencing domestic violence and mental-ill health at the same time. If you are experiencing domestic violence or abuse, help is available from the following organisations and services: Refuge – 0808 2000 237 If you need urgent help in the UK and are worried about being overheard, you can dial 999, then 55 to indicate that you cannot speak. The police will be able to assist you. For mental health support you can call the Samaritans 24-hour helpline on 116 123 or go to their website. Michaela Rogers, Senior Lecturer in Social Work, University of Sheffield and Parveen Azam Ali, Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sheffield This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

OTTO RAPPThis blog is primarily art related - for my photography please go to Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed