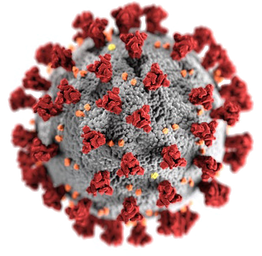

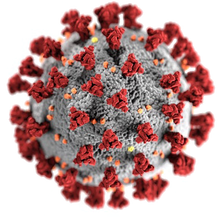

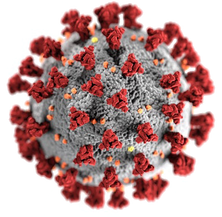

Coronavirus reinfection – what it actually means, and why you shouldn't panicZania Stamataki, University of BirminghamScientists in Hong Kong have reported the first confirmed case of reinfection with the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, reportedly backed up by genetic sequences of the two episodes of the 33-year-old man’s infections in March and in August 2020. Naturally people are worried what this could mean for our chances of resolving the pandemic. Here’s why they shouldn’t worry. Nearly nine months after the first infection with the novel coronavirus, we have very poor evidence for reinfection. However, virologists understand that reinfection with coronaviruses is common, and immunologists are working hard to determine how long the hallmarks of protective immunity will last in recovered patients. The rare reports of reinfection so far were not accompanied by virus sequencing data so they could not be confirmed, but they are quite expected and there is no cause for alarm. Inhospitable hostsOur bodies do not become impervious to viruses when we recover from infection, instead, in many cases, they become inhospitable hosts. Consider that beyond recovery, our bodies often still offer the same cell types – such as cells of the respiratory tract – that viruses latch onto and gain entry for a cosy haven to uncoat and begin producing more viruses. These target cells are not altered in any substantial way to prevent future infections months after the virus has been cleared by the immune response. If antibodies and memory cells (B and T cells) are left behind from a recent infection, however, the new expansion of the virus is rather short lived and the infection is subdued before the host suffers too much – or even notices at all. This appears to be the case with the Hong Kong patient, who did not present any symptoms of the second infection, which was discovered following routine testing at the airport. Would he ever know that he had been reinfected had he not travelled? Probably not. A more interesting question is, was he contagious during his asymptomatic second infection? There is mounting evidence that asymptomatic and presymptomatic people are contagious and this is why the sensible official advice is to wear face coverings to avoid infecting other people and to keep our distance to avoid getting infected. Coronaviruses from previous colds have endowed some of us with memory T cells that can also mobilise against the novel coronavirus, and this could explain why some people are spared severe disease.

Three potential outcomesSo how should we receive the news on reinfection of recovered individuals? There are three possible outcomes of reinfection with a similar virus: worse symptoms that lead to more severe disease, the same symptoms as the first infection, and improvement of symptoms leading to milder or no disease. The first outcome is known as disease enhancement and is noted in patients infected with similar strains of viruses such as dengue. There is no evidence for this for the novel coronavirus, despite over 23 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide. The second outcome, where the patient suffers the same disease twice, indicates that there is no sufficient immunological memory left behind to protect from reinfection. This could happen if the first infection did not require antibodies or T cells to be resolved, perhaps because other rapidly deployed immune defences were enough to control it. The final outcome is milder infection thanks to a healthy immune system that generated antibodies and memory B and T cell responses that persisted long enough to be of value during the second exposure. Given the diversity of antibody and T cell responses reported in different COVID-19 patients, we anticipate that immune protection – if efficient – may vary in different people. Of course, this has implications for the potency and duration of herd immunity, the idea that when we reach a large number of recovered patients immune to reinfection, this will protect the most vulnerable. Therefore vaccination is critical to induce and sustain protective immune responses in the long term. Vaccination can elicit more potent and longer-lasting immune responses compared with natural infection, and these can be sustained by booster vaccinations when necessary. This is why scientists were not surprised to hear of evidence of reinfection. The lack of symptoms experienced by the Hong Kong patient is very good news. Zania Stamataki, Senior Lecturer in Viral Immunology, University of Birmingham This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by Retha Ferguson from Pexels

UPDATE

Just now found on YouTube, Prof. Streek Interview. This is in German, hopefully many of my readers understand German.

Was Prof. Streek sagt habe ich schon seit einiger Zeit angenommen, in meinen Worten:

"Bald wird jeder jemand kennen der trotz Corona zwar positiv getestet, aber pumperlgsund ist" Ich bewundere wie er trotz Provokation von Maischberger trotzdem gefasst und sachlich antwortet.

Image by Jeyaratnam Caniceus from Pixabay

Does your homemade mask work?

If a surgeon arrived at the operating theatre wearing a mask they had made that morning from a tea towel, they would probably be sacked. This is because the equipment used for important tasks, such as surgery, must be tested and certified to ensure compliance with specific standards. But anyone can design and make a face covering to meet new public health requirements for using public transport or going to the shops. Indeed, arguments about the quality and standard of face coverings underlie recent controversies and explain why many people think they are not effective for protecting against COVID-19. Even the language distinguishes between face masks (which are normally considered as being built to a certain standard) and face coverings that can be almost anything else. Perhaps the main problem is that, while we know that well-designed face masks have been used effectively for many years as personal protective equipment (PPE), during the COVID-19 outbreak shortages of PPE have made it impractical for the entire population to wear regulated masks and be trained to use them effectively. As a result, the argument has moved away from wearing face masks for personal protection and towards wearing “face coverings” for public protection. The idea is that despite unregulated face coverings being highly variable, they do, on average, reduce the spread of virus perhaps in a similar way as covering your mouth when you cough. But given the wide variety of unregulated face coverings that people are now wearing, how do we know which is most effective? The first thing is to understand what we mean by effective. Given that coronavirus particles are about 0.08 micrometres and the weaves within a typical cloth face covering have gaps about 1,000 times bigger (between 1 and 0.1 millimetres), “effectiveness” does not mean reliably trapping the virus. Instead, much like covering our mouths when we cough, the aim of wearing cloth coverings is to reduce the distance that your breath spreads away from your body. The idea is that if you do have COVID-19, depositing any virus you may breathe out on either yourself or nearby (within one metre) is much better than blowing it all over other people or surfaces. So an effective face covering is not meant to stop the wearer from catching the virus. Although from a personal perspective we might want to protect ourselves, to do so we should be wearing specially designed PPE such as FFP2 (also known as N95) masks. But, as mentioned, by doing so we risk creating mask shortages and potentially putting healthcare workers at risk. Instead, if you want to avoid catching the virus yourself, the most effective things to do are avoid crowded places by ideally staying at home, don’t touch your face, and wash your hands often. Two simple testsIf effectiveness for face coverings means preventing our breath travelling too far away from our bodies, how would we go about comparing different designs or materials? Perhaps the easiest way, as demonstrated by several increasingly shared pictures or videos on social media, is to find someone who “vapes” and film them breathing out the vapour while wearing a face covering. One glance at such a picture dispels any suggestion that these face coverings stop your breath escaping. Instead, these pictures show that your breath is directed over the top of your head, down onto your chest, and behind you. The breath is also turbulent, meaning that although it does spread out, it doesn’t go far. In comparison, if you look at a picture of someone not wearing a face covering, you will see that the exhalation goes mostly forward and down, but a significantly further distance than with the face covering. Such a test is probably ideal for examining different designs and fits. Do coverings that loop around the ears work better than scarves? How far under your chin does a covering need to go? What is the best nose fitting? How do face shields compare to face masks? These are all questions that could be answered using this method. But, in conducting this experiment, we should appreciate that “vaping” particles are about 0.1 to 3 micrometres – significantly bigger than the virus. While it is probably fair to assume that the smaller virus particles will travel in roughly the same directions as the vaping particles, there is also the chance that they may still go straight forward through the face covering. To get an idea of how much this might happen, a simple test involving trying to blow out a candle directly in front of the wearer could be tried. Initially, the distance coupled with the strength of exhalation could be investigated, but then face coverings made from different materials and critically with different numbers of layers could be tried. The design of face covering that made it hardest to divert the candle flame will probably provide the best barrier for projecting the virus forward and through the face covering. Without any more sophisticated equipment, it would be difficult to conduct any further simple experiments at home. However, combining the above two tests would provide wearers with a good idea about which of their face coverings would work the best if the aim was to avoid breathing potential infection over other people. Simon Kolstoe, Senior Lecturer in Evidence Based Healthcare and University Ethics Advisor, University of Portsmouth This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fantastic gift items are found in the MET STORE

Here are a few selections from Clothing and Accessories

How we found coronavirus in a cat

Since the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, the potential role of animals in catching and spreading the disease has been closely examined by scientists. This is because the virus that causes COVID-19 belongs to the family of coronaviruses that cause disease in a variety of mammals. The evidence suggests that this virus arose in bats and my colleagues at the University of Glasgow have recently determined that the sub-type of coronavirus to which the virus belongs has been circulating in the bat population since the 1940s. So it makes sense for researchers to ponder whether the virus can be transmitted to companion animals, whether these animals can show symptoms of infection, and whether they may play any role in the epidemiology of the disease. Cats are the UK’s most popular pet – a 2019 survey revealed there are almost 11 million felines in households across the country. Public concern about felines was initially raised when tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo in New York were found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes COVID-19.

There have also been sporadic reports of cats from COVID-19 households in Hong Kong, Belgium, France, Spain and the US which have tested positive for the virus. So, could our domestic cat population be somehow involved in this pandemic here in the UK? We decided to find out. Searching for coronavirus in UK catsIn early May, my colleagues and I were given ethical approval to retrospectively test cats for SARS-CoV-2 and work soon began screening routine respiratory samples taken from cats throughout the UK. We also launched an appeal to veterinary surgeons asking for samples from suspect cases. After screening hundreds of samples, this collaborative effort eventually resulted in the detection of a cat with SARS-CoV-2 in the south of England, which had been sampled in mid-May. Further samples submitted to our veterinary colleagues at the Animal and Plant Health Agency revealed that this cat had developed an antibody response to the virus, demonstrating that it had indeed experienced a genuine infection and confirming it was not a simple case of sample contamination. Circumstances indicate that the cat contracted the virus from its owners, who had previously tested positive for COVID-19. At this point, the World Organisation for Animal Health was notified by the UK Chief Veterinary Officer and the press was alerted. We are currently preparing a paper on our findings for publication. Should I be worried about my cat?So, what does this case tell us? Our research coincided with the UK COVID-19 outbreak, focusing on cats experiencing respiratory symptoms. Our finding of a single infected individual among the hundreds screened tells us that infection in cats is relatively uncommon. This is reinforced by the fact that the other cat in the household never became infected, either by the owners or the infected cat.

Although the cat had been experiencing mild symptoms, including runny eyes and a snotty nose, these signs were consistent with feline herpesvirus infection, for which this cat also tested positive. There is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was making this cat ill and thankfully, the cat and its owners have all made a full recovery. It is important to appreciate that while, to date, about 18 million people have tested positive for COVID-19, only a handful of infected cats have been detected around the world. All available evidence suggests, therefore, that cats are not involved in spreading COVID-19. However, the importance of this type of animal surveillance work is clear, considering that a million mink have recently been culled in the Netherlands and Spain as they have been implicated in disease spread. Our suspicion in the case of cats is that feline infections simply represent a “spill over” from the human epidemic, and we are currently analysing the genome sequence of the virus from the case we found to investigate this hypothesis. Our results and those from other studies, such as work in the US showing experimentally infected cats were only transiently infected, can provide reassurance to the pet-owning public. It’s very unlikely your cat has coronavirus, and if it does, it probably won’t be involved in spreading it any further. Willie Weir, Professor of Veterinary Infectious Disease, University of Glasgow This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

OTTO RAPPThis blog is primarily art related - for my photography please go to Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed